Face-to-Face with a Wolf

A photographer’s search for the elusive predator turns into a deeper discovery about family, survival, and the fragile balance between the wild and human worlds.

No scope. No long lens. Just me and the wolf, face to face in the frozen stillness of the Canadian subarctic. The wind chill hovered around minus 46 degrees Celsius—cold enough to freeze your breath in an instant. And there he stood—powerful, calm, unblinking. His amber eyes didn’t just look at me—they looked through me. I had come in search of wolves with a camera and a question. What I found was something far more powerful.

A young male wolf looks curiously forward, directly at the newcomers on an early March morning near Hudson Bay.

I’m not a biologist, nor am I part of any conservation movement. I came to wolves through a different path—through the lens. As a photographer, I’ve spent years chasing life in wild places, hoping to capture moments that connect us. I’ve photographed grizzlies fishing in Alaska, eagles in flight over the Rockies, moose sparring in the willows. But one animal had always eluded me: the wolf. Not just rare—but almost mythical.

In January 2023, the search for wolves took me to Yellowstone National Park.

“I’m going to find the wolves,” I told my friends. What I discovered there—and in the journeys that followed—reshaped not only how I see wolves, but how I see the wild and our place within it.

As a photographer, I had come to see Yellowstone as a playground for hiking and exploration. But I quickly learned that while Yellowstone’s wolves are well known, they are not easy to spot without an experienced guide. You can try to follow the crowd, but that has never been the kind of experience I was looking for. And even when you do find them—early on a hazy morning or just before dusk as they move in search of prey—they are usually too far away to capture anything truly special through the lens.

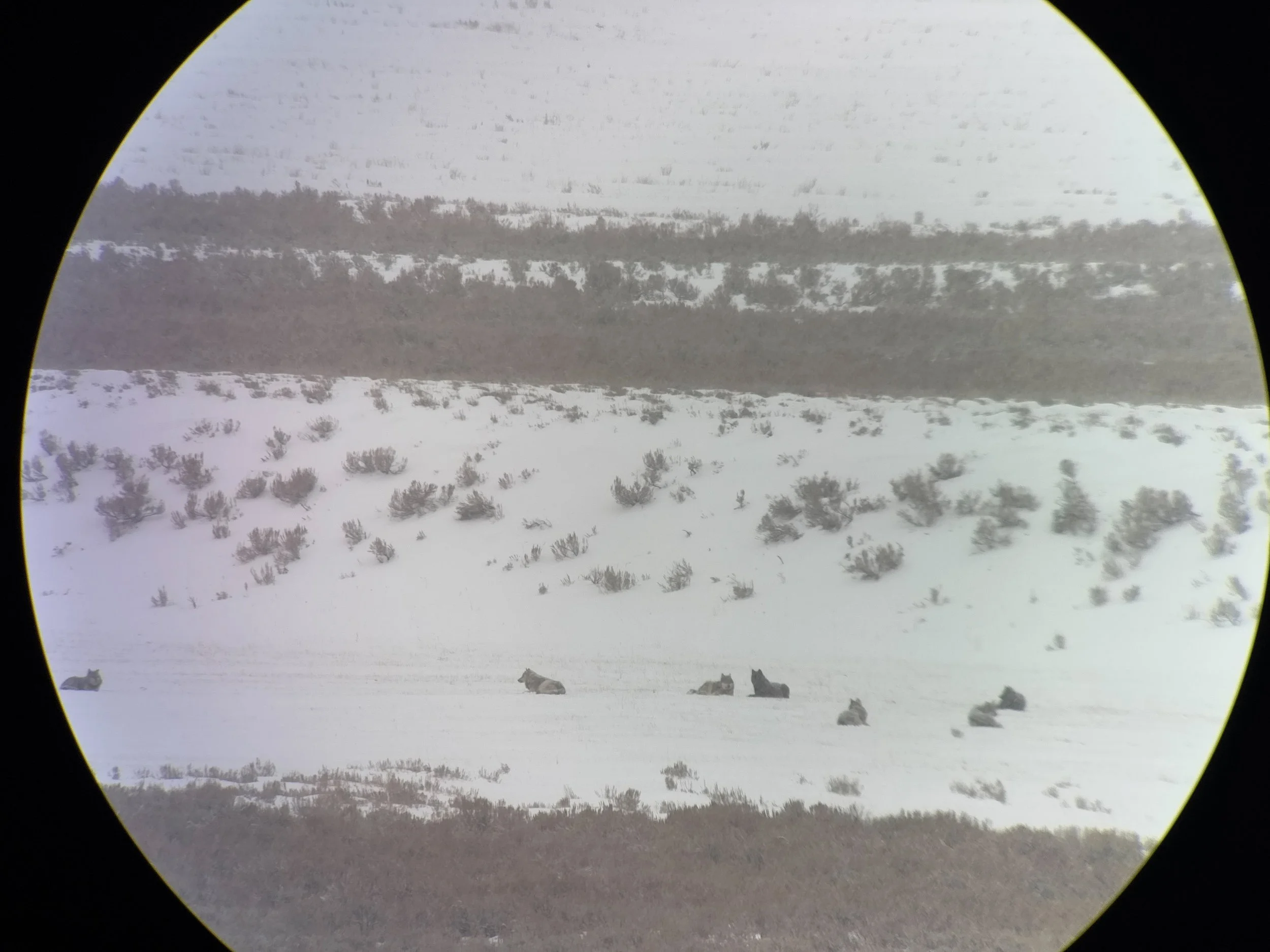

Through the spotting scope the view of the Mollie Pack as they rest in the river delta after a overnight Elk kill in the East end of the Lamar Valley.

I left that first trip without a single usable wolf photo. But I came away with something more enduring. I had heard the stories—how the reintroduction of wolves helped restore balance to a wounded ecosystem, particularly in the Lamar Valley, where unchecked herds of elk and bison had degraded the land. With wolves came balance. With balance came renewal. It felt like a modern legend—a rare moment when science and sacrifice helped set something right. Driving home, I realized I needed to know more: about wolves, their return to the West, and the complex relationship we humans have with them.

After a few more visits to Yellowstone, I began searching farther afield. In March 2024, I traveled to the Canadian subarctic—to the remote shores of Hudson Bay near York Landing. Once a hub of Canada’s fur trade, the area is now largely uninhabited, with no sustained human presence for hundreds of miles in any direction.

York Factory : On the shores of Hudson Bay, once the center of commerce for Canada.

There, I found endless coastline and rich boreal forest. Along the shore roamed wolf packs with little exposure to humans—and little fear. In this stretch of wilderness, the Opoyastian (Big Wind) pack roams a 70-kilometer sliver of land between forest and bay, split by the mouth of the Opoyastian River as it forks into the sea.

It was there, on that bright morning in the Arctic cold, that I encountered the wolf. Not through a scope or lens, but face to face. It was not the experience I expected—and it’s one I will never forget.

What I learned in the days and weeks that followed changed everything I thought I knew. Wolf packs are not random collections of predators banded together by instinct. They are families—structured, cohesive, and deeply social.

Three gray wolves stand side by side in the cold, their breath visible in the air as they pause together. For a moment, they hold their attention in our direction before turning back to join the pack.

At the center of each pack is a breeding pair and their offspring, sometimes joined by a disperser—a lone wolf, often a male, seeking a new beginning. The pack’s mission is simple: to raise and protect its young.

In Yellowstone, I had observed pack behavior from a distance, through spotting scopes. But here, on the shores of Hudson Bay, I saw something entirely different. The breeding male—often referred to as the alpha—is not just a hunter. He is a father, a protector, a partner. His bond with the breeding female is more than reproductive—it is emotional and functional. They sleep close together, care for the pups, provide discipline, and communicate through touch and body language in ways that feel remarkably familiar. In the pack, raising pups is a shared responsibility. There is a clear hierarchy, and the breeding pair lead with intention. Packs are high-functioning teams.

Wolves value play and are endlessly curious. Play teaches the young how to survive. Curiosity helps them adapt, find food, and avoid danger. Young wolves are bundles of energy. They chase, explore, and play-fight constantly—but always under the watchful eye of their elders, and always with purpose.

Along Hudson Bay, their primary prey is moose. One moose can feed a pack for over a week—but moose are dangerous. They are massive, with sharp hooves capable of killing a wolf with a single blow. Watching wolves hunt moose is like watching a team sport. Each member knows their role. Strategy, timing, and coordination are essential. A mistake can cost a life. A broken jaw or rib is often fatal. And every injury weakens the pack. Losing just one member can tilt the odds against their survival.

Grey Wolves (Canis Lupus): Once numbered in the millions across North America. By 1965 wolves were nearly eradicated in the lower 48 states, numbering less that 300 in a small pocket near our northern boarders in Michigan and Minnesota.

Since that first trip to Yellowstone in 2023, I’ve traveled often—seeking wolves, yes, but also seeking understanding. I’ve returned to northern Michigan, where I studied at Michigan Tech on the shores of Lake Superior, a landscape where wolves still roam the deep pine forests. I’ve visited the International Wolf Centers in Minnesota and Colorado, learning from researchers and biologists who have dedicated their lives to these animals. I’ve spoken with ranchers and friends here in Colorado, listening to their concerns and stories. I’ve watched wolves fish in the rivers of Alaska, and I’ve made return pilgrimages to both Yellowstone and Hudson Bay.

What began as a photographer’s curiosity has become something deeper—a deep respect for the resilience, intelligence, and emotional lives of wolves. I no longer see them as villains or heroes, but as something far more nuanced: families surviving on the edge, doing what they must to endure. In that way, they’re not so different from us.

Wolves are not just symbols of wilderness. They are reminders—of balance, of connection, of what it means to live in a world shared with others. My journey has been one of learning—not just about wolves, but about the stories we tell about them, and what those stories reveal about ourselves.